The Definitive History of Private Credit

From the days of Drexel Burnham Lambert to the "Golden Age"

Private credit is the hot thing on Wall Street right now. Not a day goes by without someone proclaiming it’s the “Golden Age” of private credit on Bloomberg. According to BlackRock, the asset class has more than tripled since 2015 to $1.6tn in global assets under management.

Some very quick definitions

In the following history of private credit, I primarily refer to private credit in the direct lending sense: a non-bank source of cashflow-based lending issued to fund private equity-backed acquisitions of companies. Put simply, direct lending is when a financial institution, other than a bank, lends money to company. Direct lenders usually make their lending decisions based on the borrower’s cash flow rather than asset base, the borrowers are typically mid-sized, and the deals are usually backed by private equity sponsors.

Private credit is a substitute product for high-yield bonds and broadly syndicated loans originated by non-bank financial institutions. Think of a private equity fund structure, with similar types of LPs, but the firm invests in debt instead of equity.

The 5 core pillars in the history of private credit

The following 5 sections could have stood as independent posts but I liked the idea of a definitive history of private credit compiled in a single repository. The 5 more important components in the rise of private credit are:

Drexel Burnham Lambert and Michael Milken creating the market for high-yield middle-market debt, and training the current vanguard of the industry.

Various regulations from the 1980s through the GFC have inhibited bank lending to mid-sized corporates and created a gap for private credit funds.

The wave of American banking consolidation has pushed traditional investment and commercial banks upmarket into larger cap financings.

Firms are staying private for longer, in tandem with the financialization of the middle market the rise of private equity as an alternative for public markets.

The post-COVID rally, LBO boom, rate hikes, and resulting hung debt more recently served as a catalyst for private credit gaining share in large-cap buyouts.

While these 5 topics follow in roughly chronological order, the rise of private credit is really a story of multiple intertwined threads. It’s been an undulating trend of exuberance, followed by catastrophe, and then regulation which led to the gradual alignment of private credit and equity over the last 50 years.

Part 1 - Drexel Burnham Lambert

Drexel is the dawn of leveraged finance

Non-investment grade bonds (aka “high yield bonds”) are credits rated BB+ (or lower) from S&P or Ba1 (or lower) by Moody’s. Well regarded companies like Tesla, Uber, and Hilton all have non-investment grade bonds outstanding. Today, they’re considered commonplace financial instruments that play a role in vanilla, diversified investment portfolios, but this was not always the case.

In the early 1970’s, non-investment grade bonds were regarded as “fallen angels.” Banks in that era rarely, if ever, originated new bond issuances with non-investment grade credit ratings. The only non-investment grade bonds in the market were bonds of “fallen angels” or companies whose credit ratings had deteriorated below the investment-grade threshold after issuance.

During his time at UC Berkeley in the mid-to-late 1960s, Michael Milken stumbled upon a series of studies from W. Braddock Hickman commissioned by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Hickman analyzed corporate bond performance from 1900 to 1943 and found that a large, diversified portfolio of low-grade bonds produced better returns than a large, diversified portfolio of high-grade bonds. The low-grade portfolio incurred more defaults, but the higher yield more than compensated for the incremental losses.

Milken had already long been a student of financial markets and Hickman’s studies supported his fledgling hypotheses with four decades of data. Milken found religion, or as modern investors might proclaim, he’d developed conviction.

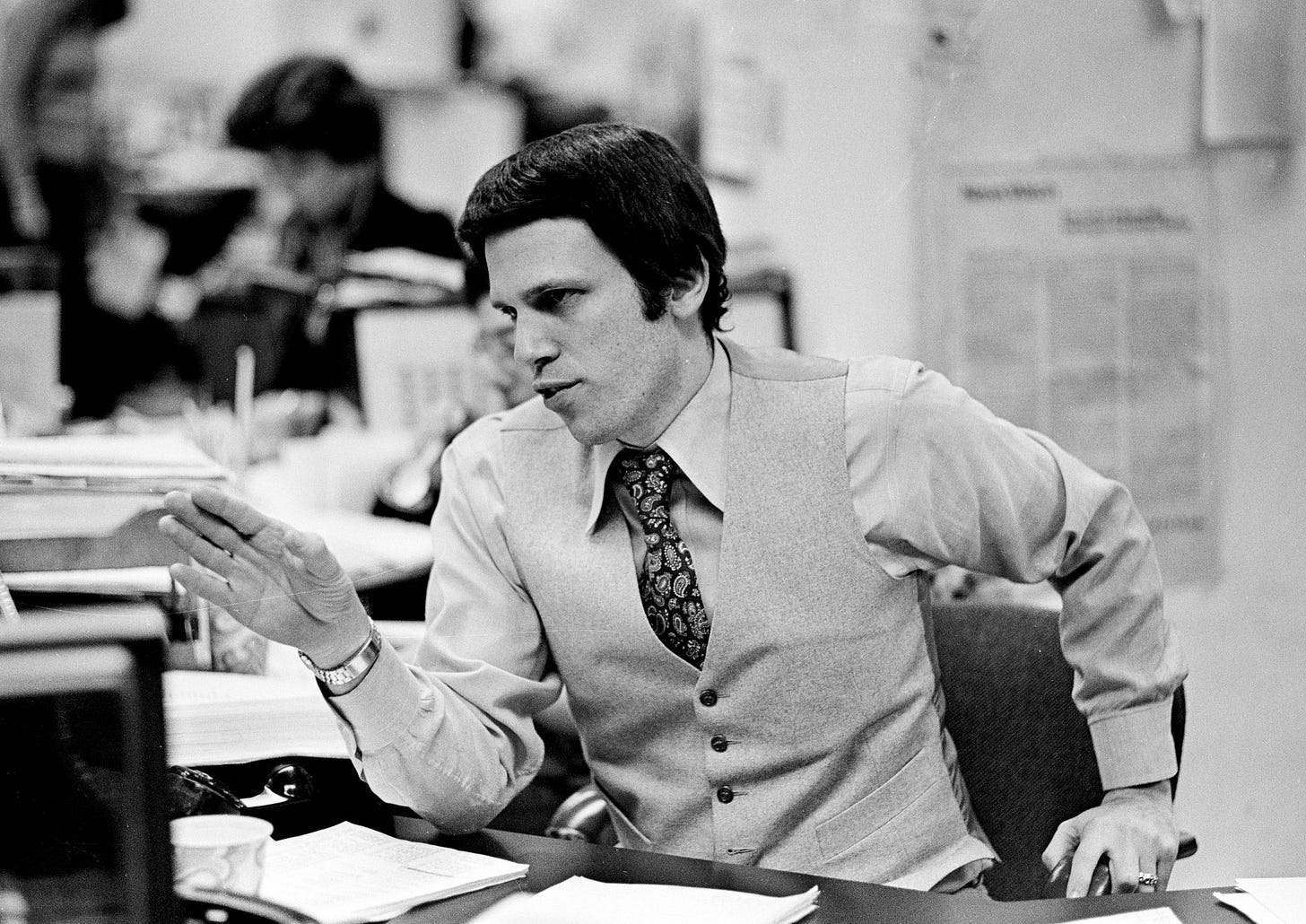

After finishing up at Berkeley and getting his MBA at Wharton, Milken joined Drexel Firestone in 1970. He immediately began to preach his gospel. Much to the disdain of his high-grade trading, and allegedly antisemitic, peers, Milken began trafficking in low-grade bonds and turning a healthy profit. Over the next few years he continued to generate profits but was viewed as a pariah and constrained to a small capital base in an isolated corner of the firm.

In 1973, Drexel Firestone was taken over by the predominately Jewish brokerage firm Burnham & Company. Founder and CEO, Tubby Burnham, quickly identified Milken’s potential and shattered the glass ceiling. Milken was given authority over a $2m portfolio and a deal for 35% of all his trading profits. In the first year, Milken’s portfolio returned 100%. For the duration of his tenure at Drexel, Milken’s 35% profit share arrangement remained.

One man’s trash is another man’s treasure

In the early 1970s, banking consolidation and the rise of the middle market had already began to press leveraged finance forward. From 1971 to 1978, the number of banking “submajors” had fallen from twenty-three to two. The submajors were historically the primary source of capital for medium-sized enterprises so the 1970s’ culling left much of the middle market without investment banking representation.

When Fred Joseph joined Drexel as co-head of corporate finance in 1974, he realized that the post-merger Drexel Burnham lacked a strong corporate identity. In pursuit of differentiation, he decided Drexel would lean into serving “medium-sized, emerging growth companies,” establishing a strategic focus that would soon dovetail nicely with Milken’s junk bond issuance.

Legend holds the term “junk bond” originated during a conversation between Meshulam Riklis of Rapid-American and Michael Milken when Milken proclaimed, “Rik, these are junk!” Riklis responded, “You are right! But they pay interest, and they sell at a discount.” To Milken’s disdain, the joke stuck.

New issuance of junk bonds kicked off in earnest in early 1977 when Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb underwrote multiple new issues of low-grade, high yielding bonds. These new issues contrasted starkly with existing fallen angels because they were rated sub-investment grade out of the gate, a banking maneuver not seen since the conglomerate boom of the 1960s. By 1977 Milken had fostered a reasonably large client base of junk bond believers. From 1974 through 1977, his clients realized impressive gains trading junk bonds of companies like Loews, Westinghouse, and Woolworth’s.

Milken’s clients were hungry for more, and in April 1977, he gave them just that with Drexel’s first new issuance of high yield debt: $30m of subordinated debentures at 11.5% for oil and gas exploration company Texas International. Drexel ranked 2nd after Lehman in 1977 with $125m in junk bond new issuance. Junk issuance was still considered a dirty business and other firms, including Lehman, were hesitant to fully commit. Drexel had no qualms about the market. As a bank, Drexel “had no franchise to protect” and junk bonds were the perfect product to serve their target client base of mid-sized growth companies.

Ascending to godhood

For the next 10 years, Michael Milken’s junk bond issuance and trading operation charged up and to the right. By 1986, Drexel had risen from relative obscurity to the most profitable investment bank on Wall Street. Milken, meanwhile, ascended to godhood. He personally collected $295m in compensation in 1986. In 1987, he raked in $550m.

Drexel’s story is a wild ride, and particularly well documented in Connie Bruck’s The Predators’ Ball. Throughout the following decade of Drexel’s reign, Milken was Midas. He’s partially, if not largely, credited with knighting modern business magnates such as Steve Wynn, Carl Icahn, T. Boone Pickens, Nelson Peltz, John Malone, Rupert Murdoch, and Ronald Perelman, all of whom Milken backed with junk bonds in their early and mid careers.

Milken was also a core pillar of the 1980s LBO boom. Working alongside the head of Drexel’s M&A group, Leon Black, Milken raised billions of dollars of high yield debt for takeovers of National Can, Revlon, Beatrice Companies, RJR Nabisco, and many others. According to a study from the University of Florida, high yield bond issuance was $300m in 1977. By 1986 issuance had ballooned to over $18bn and Drexel Burnham Lambert had 53% market share.

A dramatic decline, but a lasting impact

By the end of the decade, however, cracks began to show. In 1986, Drexel Managing Director Dennis Levine plead guilty to an insider trading scheme that ultimately implicated numerous figures across the Street including Ivan Boesky, Martin Siegel, and Michael Milken himself. Drexel denied wrongdoing for over two years, but after intense pressure from the SEC and threats of a RICO indictment from Rudy Giuliani, Drexel plead guilty to six felonies and paid $650m in fines. Michael Milken was personally indicted and subsequently imprisoned, but has since received a presidential pardon from Donald Trump. Drexel’s business quickly soured after the indictments and amidst a tough macro backdrop for high yield, Drexel filed for bankruptcy in 1990.

Despite Drexel’s explosive demise in 1990, Michael Milken left a lasting impact on Wall Street. We can attribute to his legacy the following tenants of modern American financial markets:

Emphasis on the importance of the owner-manager in corporate America.

Financialization of the middle market in partnership with private equity.

Comfort with higher levels of leverage in a company’s capital structure.

Measuring and optimizing, rather than avoiding, risk in a portfolio.

Put more simply, Drexel’s unique insight was that although smaller companies are riskier to finance, doing so is worthwhile because the increased yield will offset higher losses. Couple that with the belt tightening function of debt, the incentive alignment of private equity sponsors, and you create a compelling case for the establishment of capital markets serving middle market companies.

Michael Milken honed the art of leveraged finance and trained many in the way of his sword. Post collapse, Drexel alumni dispersed like seeds of a dandelion into the winds of Wall Street. Nearly all major players in today’s private credit landscape track their roots directly or indirectly to Drexel Burnham Lambert. The following map almost certainly misses some relevant Drexel alumni, but in general, paints a compelling portrait of Milken’s impact. Other firms had outsized impacts as well like Banker’s Trust, E.F Hutton, Lehman Brothers, and GE Capital, but at the end of the day…

…all roads lead to Michael Milken

Part 2 - Regulation and Private Credit

Basel I and the introduction of capital adequacy

The 1980s got a little crazy. On October 19th, 1987 (“Black Monday”), the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 23%. At the end of the decade, Drexel Burnham Lambert and the junk bond market collapsed. From 1986 to 1995, a full 32% of US savings and loan associations went under. Globally, Latin America experienced its own debt crisis. World governments took notice.

Although banking regulators began to focus on bank capital adequacy in the mid-1950s, modern risk-based capital guidelines really began to take shape in the mid-to-late 1980s. Congress began to establish regulatory authority over bank capital with the International Lending Supervision Act of 1983. Following the G10 central banks’ establishment the Basel Capital Accord (“Basel I”) in 1988, Congress passed the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989 and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991. The three of these acts effectively shaped the United States’ version of Basel I.

The primary theme of capital adequacy guidelines divided a bank’s portfolio of investments into different tiers based on perceived riskiness. For each risk tier, the dollar value of assets was multiplied a percentage. The sum product of these risk tiers and risk weights resulted in a risk-weighted asset total which ultimately determined how much capital (basically equity) a bank had to hold. In the initial introduction of this system, the following percentages were applied to the different categories of assets:

Cash and cash equivalents: 0% (i.e., no requirement to hold equity against cash or cash equivalents).

Short term claims guaranteed by US depository institutions: 20%.

Loans secured by first liens on one to four family residences: 50%.

Commercial loans: 100%.

This regulation made it extremely expensive for chartered banks to extend credit to companies (commercial loans), especially in private equity deals. Henry Butler and Brady Dugan summarized the impact nicely in a 1990 Washington University Law Quarterly review stating,

“The asset portfolios of many banks include loans made to corporations to finance leveraged buyouts. These loans fall into the one hundred percent risk weight category…they will discourage banks from financing leveraged takeovers.”

Defining “highly leveraged transactions”

Towards the peak of the 1980s buyout boom, the Federal Reserve Board, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (cumulatively the “Banking Agencies”), began to sharpen their pencils on LBOs specifically. In 1989 the Banking Agencies published the now rescinded OCC Banking Circular 242, Definition of Highly Leveraged Transactions. The Banking Agencies defined a highly leveraged transaction (“HLT”) as:

“(A)n extension of credit to or investment in a business by an insured depository institution where the financing transaction involves a buyout, acquisition, or recapitalization of an existing business and one of the following criteria is met:

The transaction results in a liabilities-to-assets leverage ratio higher than 75 percent;

The transaction at least doubles the subject company’s liabilities and results in a liabilities-to-assets leverage ratio higher than 50 percent;

The transaction is designated an HLT by a syndication agent or a federal bank regulator.”

According to a 2008 GAO report, the regulators in 1989 “jointly defined the term ‘highly leveraged transaction’ to establish consistent procedures for identifying and assessing LBOs and similar transactions.” Given an agreed upon definition for benchmarking, the Federal Reserve began requiring banks to report data on their highly leveraged transactions in 1990. If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.

A 1990 study from K. Hamdani at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, estimated that banks provided at least half of the total financing for US LBOs between end-1987 and mid-1989. A 1990 Bank of International Settlements study reported total bank exposure to HLTs in 1989 could have been as much as $170bn. The same study found over 300 publicly traded US-owned banks had HLT loans outstanding with the top 20 and 50 banks accounting for 75% and 95% of total exposure.

In short, banks partied like it was 1989, but came home to Mom and Dad waiting up in the living room. Commercial and industrial loans (“C&I”) as a percentage of total commercial bank credit fell from 26% in 1989 to 20% in 1994 (FRED, H8 data). As early as 1990, the impact was visible with an FOMC report noting,

“A more cautious provision of credit by lenders, reflecting regulatory pressure and investor concern about highly leveraged and other high-risk borrowers…as greater regulatory scrutiny, several prominent bankruptcies, and the collapse of the junk bond market have made many lenders reluctant to finance HLTs.” - FOMC Summary & Outlook, March 1990

In response to the HLT guidelines, leveraged finance began to popularize the now ubiquitous Term Loan B (“TLB”); a loan with very little annual amortization until a large bullet payment at maturity. It’s very difficult for commercial banks to hold these types of loans from a regulatory capital perspective, so TLBs are more likely to be purchased by non-bank financial institutions or sold by investment banks in an “underwrite and distribute” model.

Non-bank financial institutions had already begun dipping their toes into the HY bond market during Milken’s reign. Firms like MassMutual, Fidelity, and Prudential were all drawn to the alluring prospects of yield from low-grade credit. However, according to Meredith Coffey and Elliot Ganz from the LSTA, retrenchment from banks after the 1989 HLT definition (likely coupled with the aforementioned capital adequacy requirements) is reputed to have created an opening for the rise of the institutional loan market. The HLT definition was eliminated in 1992 when the Banking Agencies claimed the definition had “achieved its purposes of focusing attention on the need for banks to have strong internal controls for HLTs,” but they made sure to clarify regulators would “continue to scrutinize the transactions in their examinations.”

More growth, more guidance

The excessive lending of the 1980s had been stymied, but not for long. The mid-90s brought the dawn of commercial internet (decommissioning NSFnet) and the deregulation of the telecommunications industry (Telecommunications Act of 1996). Alongside fears of potential IT blowup once the world clock struck 2000, technology investment skyrocketed. Telecom providers called their investment bankers and brought out their checkbooks. Even CISCO made 45 acquisitions from 1995 to 2000. At the peak in 1999, telecom providers conducted $800bn of M&A. Unfortunately, not all of the credit was issued to high quality companies with scandal-ridden firms like WorldCom and Enron doing tens of billions of dollars of deals.

As the credits began to sour, the Banking Agencies spoke up. In 2001, regulators issued the 2001 Leveraged Lending Guidance (“2001 Guidance”). They remarked that “a significant share of the recent problem credits is associated with leveraged financing” and that the Banking Agencies were “issuing this guidance to bankers and examiners to describe more fully supervisory expectations regarding sound practices for leveraged financing activities.”

They redefined “leveraged transactions” more broadly as transactions where leverage ratios “significantly exceed industry norms for leverage.” The regulators also commented that much of this lending occurs in the middle market. The 2001 Guidance, however, was too vague to be impactful. The Banking Agencies would be significantly more prescriptive in their 2013 update.

Guidance speaks louder than laws

I’ll fast-forward through the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”) which is detailed at length here, here, here, and here, and briefly here. In the wake of the GFC, the Banking Agencies decided to revise their original 2001 Guidance. In 2013 they put forth the Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending (“2013 Guidance”). This guidance was significantly more extensive, detailed, and prescriptive compared to the 2001 Guidance.

The agencies wrote that “a poorly underwritten leveraged loan that is pooled with other loans or is participated with other institutions may generate risks for the financial system.” They called out the absence of maintenance covenants, and the inclusion of PIK toggles. They even took a swipe at banking tech stacks noting that “management information systems have proven less than satisfactory in accurately aggregating exposures on a timely basis.”

Perhaps most importantly the agencies included numerical demarcations (“bright lines”) for appropriate underwriting standards:

“[Leverage] in excess of 6X Total Debt/EBITDA raises concerns for most industries;”

“[Supervisors commonly assume] the ability to repay at least 50 percent of total debt over a five-to-seven year period.”

Some banks took head. Some didn’t. Over the following two years, banks begin to receive Matters Requiring Attention notices (“MRAs”) from regulators. The Fed’s seriousness became clearer when in May 2014 a senior Fed official publicly remarked that lending standards “have continued to deteriorate in 2014” and that “stronger supervisory action” may be needed.

In September 2016, Credit Suisse received a Matters Requiring Immediate Attention Notice (“MRIAs”). The next day, Credit Suisse pulled out of a leveraged loan financing for Hellman and Friedman’s acquisition of Grocery Outlet Inc.

To clarify, the 2013 Guidance only applied to financial institutions that fall within the regulatory scope of the three major Banking Agencies (OCC, Federal Reserve, and FDIC). This guidance did not apply to non-bank financial institutions like private credit funds.

In 2017, Senator Pat Toomey formally questioned whether the 2013 Guidance constituted a rule under the Congressional Review Act. The Banking Agencies backed down and clarified the guidance was simply supervisory guidance and not a rule. The impact, however, was clear. An LSTA analysis of Refinitiv LPC data shows that in 2013 non-bank financial institutions held 14% bookrunner market share in the middle market sponsor league tables. By 2019, that figure had topped 41%.

Just a few more rules

The G10 central banks met again throughout 2010 and 2011 to discuss and refine their accords (“Basel III”) in response to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Basel II had superseded Basel I in 2004, but Basel III was a more notable update for our discussion.

In 2013, the Federal Reserve proposed two major rules in order to implement Basel III: (1) a minimum leverage ratio calculated as Tier 1 capital divided by total leverage exposure and (2) a minimum liquidity coverage ratio calculated as high quality liquid assets divided by net cash outflows. The leverage ratio requirement is, to some extent, an evolution of the 1980s capital adequacy requirement. The liquidity coverage ratio (“LCR”) was novel as it represented the first standardized liquidity requirement for large banks. LCRs disproportionately shifted the lending scale in favor of highly liquid assets like government debt and away from less liquid assets like middle market commercial loans.

In addition to imposing a colossal administrative burden with 2,300+ pages of regulation, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 included two specific sections which accelerated the rise of private credit: Section 941, concerning risk retention, and Section 631, known as the Volcker Rule. The original interpretation of the Volcker Rule prevented banks from purchasing the debt securities of CLO vehicles which further limited bank involvement in leveraged finance, although that interpretation was overturned in 2018.

More importantly, risk retention maintained that “securitization sponsors retain not less than a 5% share of the aggregate credit risk of the assets they securitize.” Because banks have to hold 5% of credit risk that they originate, and levered commercial credit risk is extremely expensive from a capital adequacy and liquidity perspective, Dodd-Frank set a firm upper limit to bank participation in the LBO lending business and leveraged finance more broadly.

The net impact of regulations like Dodd-Frank and Basel III was well summarized by Ares in a February 2020 whitepaper:

“As a result, coming out of the GFC, banks narrowed their lending products (especially in financing illiquid assets), became more risk averse, shed staff and allowed legacy businesses to be run-off or be sold. [The shift to an ‘underwrite and distribute’ model] accelerated post the GFC…non-banks became increasingly important sources of capital for non-investment grade or leveraged loan borrowers.” - Ares, February 2020, The Rise of Private Markets

Part 3 - Banking Consolidation

According to the FDIC, there were 14,434 insured commercial banks in the US in 1980. By 2022, that figure had fallen over 70% to 4,136. Consistent with our previous theme, regulation played a large role. According to a 2012 staff working paper from the Fed’s Finance and Economics Discussion Series,

The Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 allowed branch banking beyond one state and throughout the United States, and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 (Financial Services Modernization Act) allowed banks to enter other financial markets and provide additional financial services.

Over the last 40 years, the US banking industry has undertaken an M&A spree that rivals the LBO barons of the 1980s and the telecom cool kids of the 1990s. From 1999 to 2024, the FDIC tallied a total of 8,254 “business combinations” between commercial and industrial banks, savings and loans institutions, thrifts, and credit unions.

Data compiled by S&P Global shows that the top 4 US banks (JP Morgan, Bank of America, Citibank, and Wells Fargo) account for over 35% of all US bank deposits. The top 15 banks hold over 56% of US bank deposits, a remarkable fact when we recognize there are still over 4,100 distinct banks in this country.

Given capital adequacy guidelines and risk retention rules, the banks are limited in the total volume of non-investment grade corporate credit they can originate. They’ve taken the opposite of Fred Joseph’s approach and have reoriented their strategic focus upmarket. It is equally time intensive to originate a $2bn loan as a $200m loan, but 10x more lucrative. Additionally, large corporate clients who need multibillion dollar credit issuances are likely to generate fees for the bank across other banking services like M&A advisory, equity capital markets, and treasury management. As banks have narrowed in on scale banking, they’ve let go of headcount and processes historically geared towards originating smaller cap loans and banking the mid-market.

For the banks, leveraged lending is now a scale game: originate large-cap issuance, syndicate to CLOs, retain the minimum on balance sheet, and collect transaction fees.

Part 4 - Financializing the “Mid-Market”

Banks have been all but barred from capitalizing on the fundamental thesis Michael Milken identified in the 1970s: the middle market warrants financialization.

The middle market is a rapidly growing slice of America

The National Center for the Middle Market defines mid-market companies as those with between $10m and $1bn in revenue. It’s a wide range but the organization’s philosophy is that small business (less than $10m in revenues) is the media darling with representation from the SBA, and big business (over $1bn in revenues) is the America’s headline act.

JP Morgan segments this market more narrowly including businesses between $11m and $500m in revenues. In their 2023 report titled The Middle Matters, JPM states the mid-market is comprised of 300,000 businesses generating $13tn in revenue and accounting for 30% of private sector jobs. Other reports cite 200,000 businesses.

No matter how you slice it, the middle market is big. The companies are also growing more quickly that their large-cap peers. Mike Larsen of Cambridge Associates remarked in a PEI article that “median revenue compound annual growth rate in the small-cap space is 10%…in the mid-cap market that figure is 8%…in the large-cap space it falls to 5%.” Private equity, and by proxy private credit, has taken notice. Pitchbook data shows that the number of US middle market companies backed by private equity has increased from 1,700 in 2000 to almost 9,000 by 2020. Since banks have been saddled with regulation disincentivizing mid-market commercial lending, private credit has financed this sizeable market’s growth.

Companies are staying private for longer

According to research from the American University, the number of publicly traded US companies has fallen roughly 50% from 8,090 companies in 1996 to 4,266 companies in 2019. Data from the University of Florida shows that the average age of a new public technology company has nearly tripled from 4.5 years in 1999 to 12 years in 2020. The following McKinsey analysis shows that small companies rarely go public anymore:

The primary reasons companies are choosing to remain private for longer are twofold: (1) heightened regulatory obligations associated with becoming a public company in the aftermath of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002; and (2) proliferation of private equity as an alternative source of capital to public equity markets. M&A, often tied to private equity, has also played a role. In 2022, $1.2tn was raised in public capital markets. The private markets raised almost 3x that figure with $4.5tn in total capital.

There’s also a general sentiment that public markets investors on Wall Street have become more fixated on quarterly results. “Beat and raise” is a hard game to master as a less mature company. The combination of these factors often leads firms to question whether it makes sense to go public when the process is so expensive and private capital is so abundant.

Part 5 - Covid, Rates, and Hung Debt

When Covid-19 shut down the global economy in March 2020, markets froze. The S&P 500 cratered 30%+ from February 14th to March 20th. But fueled by $800bn in completely non-recourse PPP loans and $900bn in direct deposits to individual checking accounts, markets came roaring back. GME stock hit $483/share and Bored Apes passed a 150 ETH floor price. Institutional markets were hot too. Every analyst on Wall Street had moved back into his parent’s house with nothing to do but play Call of Duty: Warzone and screen the internet for LBO targets.

2021 was a good year on Wall Street. Total CLO sales, closely correlated to leveraged loan issuance, almost tripled in 2021 to $430bn. Profit across the top 6 investment banks doubled to $170bn.

Then the Fed raised interest rates.

Hung debt really hurts

Bank debt issuance for LBOs typically works as follows: A bank (e.g., Morgan Stanley) gets a call from an important client (e.g., Elon Musk) who says he wants to LBO an exciting tech company (e.g., Twitter). In order to win the mandate and help Elon feel more secure in the availability of his financing, Morgan Stanley will commit to issue the $13bn of debt at a guaranteed price. MS temporarily commits a large portion of this debt to its balance sheet, but it's not worried because it will quickly sell down the position to hungry public credit market investors.

Elon started buying shares of Twitter in January 2022. Assuming it took him about one month to really get serious, we can imagine Morgan Stanley committed to back his corporate takeover sometime in February 2022 when the Federal Funds Effective Rate was approximately 8 bps (0.08%). With impeccably poor timing, the US Federal Reserve announced on March 16, 2022 it would begin raising interest rates. For 11 straight quarters the Fed proceeded to hike interest rates in a nearly unprecedented flurry of monetary tightening.

Once rates started going up, nobody wanted to buy Twitter debt at the price Morgan Stanley agreed to. Elon Musk was similarly stuck with his Twitter buyout and therefore had no intention of cutting his banks any slack. Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, Barclays, and Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group were saddled with billions of unattractive, highly-leveraged corporate debt. Their balance sheets were frozen and they basically pulled out of new LBO underwriting for a period of 18 months while they sold off loans at significant losses.

Twitter is just one example of a hung deal from the post-COVID buyout boom. In total according to Bloomberg, banks mounted over $80bn of hung debt throughout the course of 2022.

Private credit emerged a victor from the hung debt kerfuffle. Bloomberg reported a group of private credit funds including Oak Hill, Carlyle, and KKR turned a 30%+ IRR on preferred equity issued in the Citrix deal. More importantly, private credit started to get calls on historically unprecedented deals like Oak Hill’s $5.3bn financing for Vista’s portfolio company Finastra. Industry research from the Alternative Credit Council found that private credit fund managers lent $330bn+ in 2022, up 60% from the $200bn lent in 2021.

The staggering statistics on individual deals, private credit deployment, and fundraising have led the market to crown this era as the “Golden Age” of private credit.

What should we make of private credit?

In the beginning Drexel created leveraged finance. Now the non-investment grade market was formless and empty, darkness was over the credit ratings of fallen angels, and Michael Milken was hovering over his desk. And Milken said, “Let there be non-investment grade new bond issuance,” and there was non-investment grade new bond issuance.

Then came the Basel Accords, Dodd-Frank, and HLT Guidelines. All of which inhibited banks from lending on a cashflow basis to mid-market companies in highly leveraged private equity-backed transactions. Non-bank financial institutions, like private credit funds, eagerly filled the void.

All the while, banks consolidated, reoriented their focus to large-cap credit, and shed mid-market origination resources. Private equity took notice. Armed with continually increasing coffers of AUM multiplied by non-bank leverage, the PE firms began to aggressively deploy capital into the middle market.

Finally, a stimulus-inspired boom in LBOs crashed into a poorly timed central banking volte-face which cleared the competitive landscape for private credit to mount its most recent foray upmarket.

Was this a mistake?

One might read the history of private credit and come to the conclusion that misguided regulation boxed out traditional banks and paved the way for shadow banks to finance the private markets. There’s an element of truth, but this is not a bad thing for the broader financial markets.

The consequences of Basel, Dodd-Frank, and HLT might have been unintended, but the result strengthens the economy. While I candidly believe less is more when it comes to financial regulation, private markets might have even evolved in this direction without regulation.

Finance 101 states “do not borrow short, to lend long.” Private credit largely fixes the asset-liability mismatch that has crippled financial institutions as recently as SVB and First Republic in 1H’23.

Banks gather assets from consumer deposits which are callable at any time and prone to flight in unison. Private credit lends from a capital base of long-term assets. University endowments and pension funds with 50- and 100-year investment horizons commit capital to private credit funds with 10-year terms. Matching long-term, illiquid credits with non-bank financial capital absorbs systematic risks and produces a more resilient financial system.

Even Michael Milken, the progenitor of high-yield bank issued credit himself, believes in the wake of the SVB collapse we’ll see “a substantial increase in private credit [and other asset allocators] with long-term asset views.”

Citations:

First, I want to put out a special thanks to three sources that I found particularly useful in drafting this history of private credit:

Connie Bruck’s, The Predators’ Ball: The Inside Story of Drexel Burnham and the Rise of the Junk Bond Raiders. This is an exhilarating read on the rise and fall of Drexel written by someone who seemingly has a practitioner’s grasp of finance.

The Handbook of Loan Syndications and Trading, 2nd Edition. This is a slightly less exhilarating read, however, despite its textbook appearance it reads somewhat like a novel. I consulted multiple chapters in the book, but Chapter 14 on Public Policy and the Loan Market by Meredith Coffey and Elliot Ganz was particularly helpful in getting a handle on relevant regulations.

Ares’ Feb 2020 whitepaper, The Rise of Private Markets: Secular Trends in Non-Bank Lending and Their Economic Implications. This whitepaper, along with the early 2018 version, laid out the history in a very digestible manner and served as a loose framework for this piece.

More links, citations, and papers:

The following is offensively unorganized but I was shooting for comprehensiveness rather than MLA formatting.

Livingston and Williams, “Drexel Burnham Lambert’s bankruptcy and the subsequent decline in underwriter fees.” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 84, no. 2, May 2007, pp. 472–501, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.03.006.

Capital Allocators with Ted Seides: Episodes with Doug Ostrover, Tim Lyne, and Kipp DeVeer

https://www.nytimes.com/2005/02/06/business/yourmoney/the-drexel-diaspora.html

https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/post-crisis-decline-bank-lending

https://www.gao.gov/assets/a280152.html

https://www.wsj.com/articles/credit-suisse-loans-draw-fed-scrutiny-1410910272

https://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-win-fight-over-risky-looking-loans-1449110383

FOMC Summary and Outlook, March 21, 1990

Leveraged Financing Guidance, April 9, 2001

Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending, March 22, 2013

BIS Economic Papers, Banks’ Involvement in Highly Leveraged Transactions by C.E.V. Borio, October 1990

The Impact of Recent Banking Regulations on the Market for Corporate Control, Henry N. Butler and J. Brady Dugan, 1990 Washington Law Review

Consolidation and Merger Activity in the United States Banking Industry from 2000 through 2010, Robert M. Adams, 2012 Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Federal Reserve Board

The Volume of Corporate Bond Financing Since 1990, W. Braddock Hickman, NBER 1953

St. Louis Fed H8 data

FDIC banking data

Risk-Based Capital Adequacy Guidelines: A Sound Regulatory Policy or A Symptom of Regulatory Inadequacy?, Fordham Law Review 1995

Wikipedia pages for Drexel Burnham Lambert, Apollo, Ares, GSO, Crescent Capital, TCW, and Basel III

https://www.privateequityinternational.com/the-march-of-the-us-mid-market/

Dissecting the Listing Gap: Mergers, Private Equity, or Regulation?, Journal of Financial Markets, Forthcoming, Ali Sanati, American University

https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/50-largest-us-banks-by-total-assets-q3-2023-79625289

JP Morgan, Exploring the Diverse Middle Market Business Landscape, 2023

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20130702a.htm

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20131024a.htm

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-12-27/wall-street-s-6-biggest-banks-hit-1-trillion-profit-in-10-years?sref=24XVM4Da

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-10/why-hung-debt-is-still-hurting-banks-lessons-from-twitter-brightspeed-deals

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-17/wall-street-s-hung-debt-swells-to-43-billion-as-tenneco-closes

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-11-20/oak-hill-carlyle-kkr-win-big-on-citrix-buyout-as-banks-nurses-losses

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-10-07/morgan-stanley-led-banks-face-500-million-loss-on-twitter-debt

https://acc.aima.org/article/press-release-private-credit-funds-report-growth-in-activity-as-other-lending-markets-retrench.html

Author’s Note: I left out a variety of topics which might be decent conversations for future pieces. It’s probably worth going in more depth on the rise of private equity, shifting allocations to alternatives, the Yale model, and perhaps most importantly, reasons why private credit as a product is attractive to private equity firms (rather than simply a product filling a void left by the banks). But I had to cut this post eventually… Let me know what you think!

What a great historical overview! Thanks

Thanks so much for this piece, Van. I was looking for something exactly like this for the past 6 months. It aslo pairs very well with the Capital Allocators podcast episode with the head of Ares Credit, Kipp deVeer.